Archives

- 01/01/2004 - 02/01/2004

- 02/01/2004 - 03/01/2004

- 03/01/2004 - 04/01/2004

- 04/01/2004 - 05/01/2004

- 05/01/2004 - 06/01/2004

- 06/01/2004 - 07/01/2004

- 07/01/2004 - 08/01/2004

- 08/01/2004 - 09/01/2004

- 09/01/2004 - 10/01/2004

- 10/01/2004 - 11/01/2004

- 11/01/2004 - 12/01/2004

- 12/01/2004 - 01/01/2005

- 01/01/2005 - 02/01/2005

- 02/01/2005 - 03/01/2005

- 03/01/2005 - 04/01/2005

- 04/01/2005 - 05/01/2005

- 05/01/2005 - 06/01/2005

- 06/01/2005 - 07/01/2005

- 07/01/2005 - 08/01/2005

- 08/01/2005 - 09/01/2005

- 09/01/2005 - 10/01/2005

- 10/01/2005 - 11/01/2005

- 11/01/2005 - 12/01/2005

- 12/01/2005 - 01/01/2006

- 01/01/2006 - 02/01/2006

- 02/01/2006 - 03/01/2006

- 03/01/2006 - 04/01/2006

- 04/01/2006 - 05/01/2006

- 05/01/2006 - 06/01/2006

- 06/01/2006 - 07/01/2006

- 07/01/2006 - 08/01/2006

- 08/01/2006 - 09/01/2006

- 09/01/2006 - 10/01/2006

- 10/01/2006 - 11/01/2006

- 11/01/2006 - 12/01/2006

- 12/01/2006 - 01/01/2007

- 01/01/2007 - 02/01/2007

- 02/01/2007 - 03/01/2007

- 03/01/2007 - 04/01/2007

- 04/01/2007 - 05/01/2007

- 05/01/2007 - 06/01/2007

- 06/01/2007 - 07/01/2007

- 07/01/2007 - 08/01/2007

- 08/01/2007 - 09/01/2007

- 09/01/2007 - 10/01/2007

- 10/01/2007 - 11/01/2007

- 11/01/2007 - 12/01/2007

- 12/01/2007 - 01/01/2008

- 01/01/2008 - 02/01/2008

- 02/01/2008 - 03/01/2008

- 03/01/2008 - 04/01/2008

- 04/01/2008 - 05/01/2008

- 05/01/2008 - 06/01/2008

- 06/01/2008 - 07/01/2008

- 07/01/2008 - 08/01/2008

- 08/01/2008 - 09/01/2008

- 09/01/2008 - 10/01/2008

- 11/01/2008 - 12/01/2008

- 01/01/2009 - 02/01/2009

- 04/01/2009 - 05/01/2009

- 07/01/2009 - 08/01/2009

- 09/01/2009 - 10/01/2009

- 10/01/2009 - 11/01/2009

- 11/01/2009 - 12/01/2009

- 12/01/2009 - 01/01/2010

- 03/01/2010 - 04/01/2010

Utopian Turtletop. Monsieur Croche's Bête Noire. Contact: turtletop [at] hotmail [dot] com

Wednesday, May 31, 2006

I haven’t posted on unusual web searches that have led people to this blog, but one today was poignant: a Google search on “song for when someone dies.”

The closing, valedictory song of Concert for George is a piece of Tin Pan Alley that I hadn’t heard, “I’ll See You in My Dreams” by Gus Kahn and Isham Jones. A sweet wistful bit of mourning for George. It struck me that I couldn’t think of a rock song that would have sounded so sweet and sad.

According to the booklet notes for the terrific album The McGarrigle Hour, Rufus Wainwright sang Irving Berlin’s lovely wistful “What’ll I Do?” at his grandmother’s funeral. Another apt choice.

But both songs ring slightly wrong too, because they’re overtly about romantic love.

The characters in that flick “The Big Chill” played the Stones’ “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” at another character’s funeral -- seemed sardonic.

I heard a friend sing an overpoweringly dark and guttural version of Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” at his rakish father’s funeral, because one drunken night years before his father asked him to. Not what I would choose for myself or anybody else, but from what I know of the deceased, it seemed appropriately sardonic.

“Dream a Little Dream of Me” would be spooky and sweet. Romantic too, but slightly less exclusively so than the others.

“Golden Slumbers” by the Beatles. It would give a meaningful context to the line, “Once there was a way to get back homeward.” A lullaby might make sense.

I’ve thought about recording Michigan’s alma mater, “The Yellow and Blue,” as a tribute to deceased Michigan relatives, a stately melody with pagan words.

The first time I heard the Gershwins’ “They Can’t Take That Away” was the day Fred Astaire, who introduced the song, died. A college DJ played Sarah Vaughan’s magnificent version and dedicated it to Fred before resuming regular college radio programming (reggae). It was a great tribute.

“The Way We Were” is a beautiful song but perhaps too awkward to acknowledge the rose-colored glasses of memory at a funeral.

“Danny Boy” might make sense.

Again, too much romantic love, but the great Arlen-Harburg tune “Last Night When We Were Young” deals with the question of the collapsible nature of time in memory very beautifully.

Lots of religious songs -- “Just a Closer Walk with Thee,” “I am a Pilgrim,” “In the Sweet By and By” -- many others.

My friend Johnny H used to sing a mournful country waltz with the tag line, “The best of friends must one day part, so why not you and I, my love, so why not you and I?” That’s all I remember of the song, I don’t know where he got it, and Google turns up nothing. This might be my favorite choice, but I don’t remember enough of it.

My dad wants a cousin of my mom’s with a beautiful baritone voice to sing “Taps” at his funeral. Dad’s a vet. He’s starting to make his plans.

Dear Googler from Ontario, I am sorry for your loss.

I’d love to hear about it if anybody has suggestions or any songs you’d like sung at your funeral.

Monday, May 29, 2006

asterisk

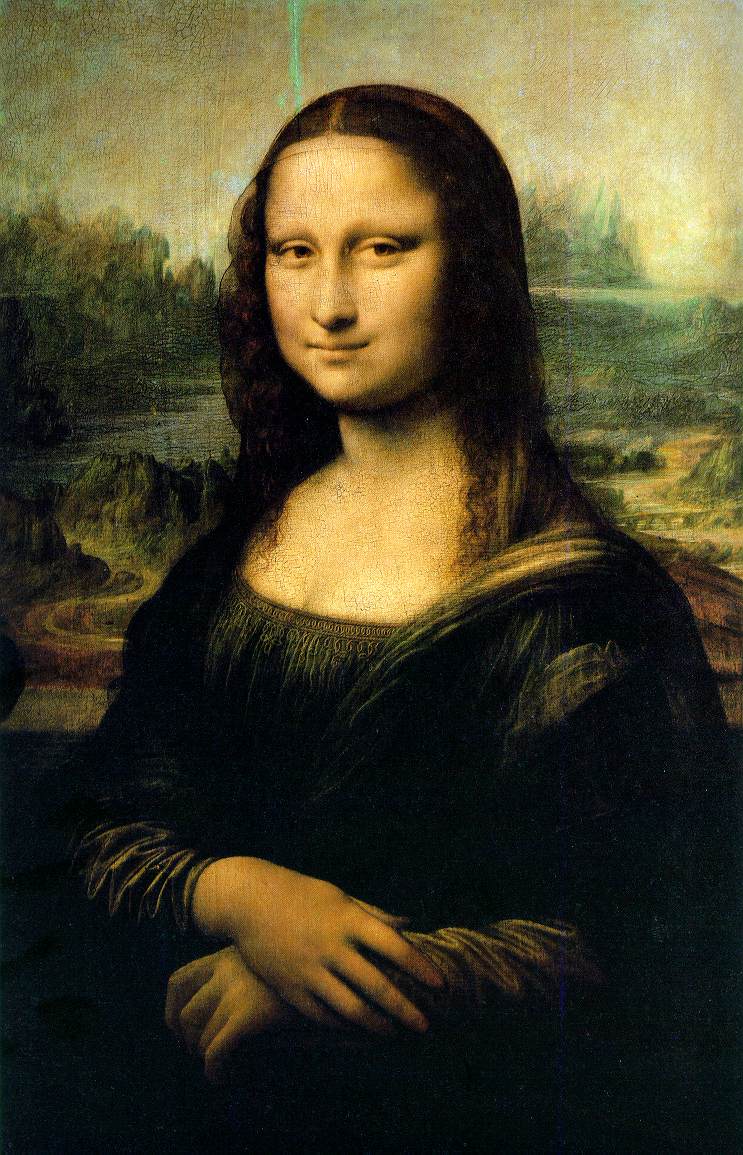

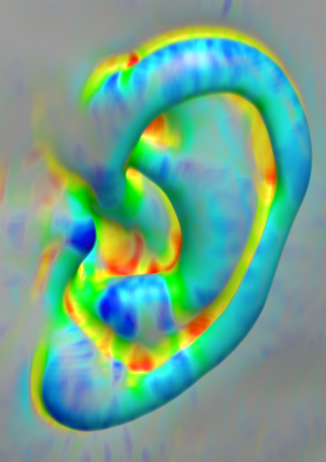

If we're going to apply asterisks to baseball players' accomplishments, let's begin with the records of the Segregated Era, where great players like Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb benefited from not having to hit the pitching of great players like Satchel Paige (above right).

Sunday, May 28, 2006

[and then 3rd thought]

If Stephin Merritt were serious about alluding to white pop culture with his music, 19th century parlor songs would have been a much better place to start than the Tin Pan Alley-Broadway-Hollywood tradition, which was full of jazz, blues, and other African American influence, and a number of whose top songwriters were African American -- Fats Waller, James P. Johnson, Eubie Blake, Spencer Williams, the Johnson brothers, Duke Ellington, and Billy Strayhorn, to name a few.

I was thinking about this the other day, and the first song that popped into my head as a Tin Pan Alley survival of the parlor song was Irving Berlin’s classic “What’ll I Do,” but then I remembered that Berlin borrowed some of the melody and a lot of the feel from a 19th century Yiddish song from Russia called “Vu Is Dus Gesele (Where Is the Little Street).” (Jewish American opera star Jan Peerce recorded a beefy orchestral version that’s available on The Yiddish Dream: A Heritage of Jewish Song.) Which may or may not qualify it as a “parlor” song; only the well-to-do in the shtetl had parlors. And white supremacists would disqualify the song because of its Jewish provenance.

It’s not a parlor song, but Ronnie Gilbert’s fierce version of a 19th century Lincoln campaign song on the various-artists collection Songs of the Civil War changed my conception of “indigenous” white pop music. A galloping waltz, Gilbert sings it with a fire that seems completely congruent with the tune as well as the abolitionist sentiment of the words. The parlor songs were highly sentimental, dripping with emotion, about death and memory and family, about love won and lost and missed. It seems that most of the people who assay the stuff now either come from a classical tradition that sacrifices verbal connection to vocal tone, or, more recently, an “indy” tradition that is too irony-laden for the material. Gilbert shows another way. It couldn’t be Merritt’s way, but I’ve learned from it.

My own interest in sentimental 19th century white pop material may be influenced from having grown up living with my grandparents in the summers. Their parents were small-town American Victorians, and in recent years I have found 19th century white pop artifacts of my grandfather’s ancestors in my parents’ house.

My grandparents were total jazz-age kids, my grandma a flapper -- they loved to dance and party. I once asked my grandpa if he ever saw his parents dance. His mother sang to him when he was a child, but no, he never saw them dance.

2nd thought immediately after posting: It could well be that Ronnie Gilbert's roar may not be indigenous to 19th century white pop singing at all, but influenced by African American gospel and pop. I'm not aware of any research into 19th century vocal timbre. Anybody who knows anything about that, please let me know in comments or via email. Thanks!

3rd thought: Gilbert's roaring isn't gravelly in the style of Etta James or Bobby "Blue" Bland -- it's more of an orator's roar with a highly accentual rhythm in the singing -- in fact, "roaring" may be overstating -- "fervent" may be closer. From what I've read of it, early 20th-century white American oratory could be quite intense; I imagine 19th-century could as well.

The song I'm thinking of, by the way, is "Lincoln and Liberty"; here is the tune and a version of the lyrics that differs in places from Gilbert's. And here's something about the probable lyricist, Jesse Hutchinson.

Friday, May 26, 2006

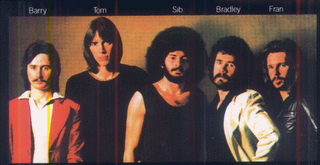

Congrats to my friend John de Roo (2nd from left, almost 25 years ago) for winning Honorable Mention in the 2006 Telluride Troubadour contest. I’ve been an ardent fan of his songs for 26 or 27 years now, and his singing and guitar and harmonica playing for longer.

(I’ve posted this pic before; gotta find another one from Back Then. I’m on the right, regular Turtletop correspondent Jay Sherman-Godfrey, a/k/a JSG, is between us; ace drummer and occasional Turtletop correspondent Dave Lewis on the left. Our first gigs -- 9th grade for all of us but Jay, who was in 8th -- were in 1978. Our first bar gig was 1981; we lied about our age. A bunch of our friends snuck in somehow too. Funny -- now I don't remember how we got into songwriting, what our first originals were. I do remember that I didn't write any worth remembering until senior year -- John & Jay wrote good ones earlier.)

Thursday, May 25, 2006

1. “Long Black Limousine” -- Elvis from the 1969 Memphis sessions. Builds up to feverish cry of grief, as “my heart and my dreams are with you on that long black limousine.” Sometimes it makes me cry.

2. The R&B cover of Bohemian Rhapsody 10 years ago or so was chilling. Quite high in restraint, and hugely effective.

3. “Leader of the Pack” -- the Shangri-Las. As in opera, you see the death happen in the present. Unlike opera, it’s the guy who dies. Like opera, the one who dies is from the wrong side of the tracks. This one makes me cry too.

4. “My Darling Nellie Gray” -- 19th century song about a couple split up when their owner sells one of them to another master, and then Nellie dies before the narrator can meet her again. Louis Armstrong with the Mills Brothers sang it with perfect restraint and delicacy.

5. “East Texas Red,” written by Woody Guthrie, though I’ve only heard Arlo’s version. Can’t get more hard-bitten than the conclusion of this song, when after killing Red his killers sit down and eat their stew. Arlo sings it with the perfect stoicism of the classic balladeer.

6. “St. James Infirmary.” There’s a blog devoted to the song. (The song and New Orleans. The song and New Orleans and music in general. But a lot about the song.) Louis Armstrong’s 1929 recording is the earliest known version, and it’s wonderful; I wrote about a hair-raising live version of it a year and a half ago.

7. “I Come and Stand at Every Door,” words by Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet, music uncredited but probably an Irish tune put to the words by Pete Seeger; I’ve only heard the Byrds’ gorgeous version; my band has played it too, in a medley with “God Bless America.” The narrator is a child who was killed at Hiroshima. The standard translation appears to be a bowdlerization, but still overwhelming. “My hair was scorched by swirling flame, my eyes grew dim, my eyes grew blind.” I found another translation that sounds more like other Hikmet poems I’ve read (and I’ve never seen the poem in any collection of Hikmet translations):

Kiz Cocugu---------------------Little Girl

Kapilari calan benim ---------It's me who knocks

kapilari birer birer. ----------the doors one by one.

Gozunuze gorunemem -------You can't see me

goze gorunmez oluler. ------the deads are invisible.

Hirosima'da oleli -------------It has been around ten years

oluyor bir on yil kadar. -----since I've dead in Hiroshima.

Yedi yasinda bir kizim, -----I'm seven years old

buyumez olu cocuklar. -----dead children do not grow.

Saclarim tutustu once, -----First my hair caught fire,

gozlerim yandi kavruldu. --my eyes burnt.

Bir avuc kul oluverdim, ----I've turned into a handful of ash,

kulum havaya savruldu. ----and that was scattered into the air.

Benim sizden kendim icin --I don't ask you for anything

hicbir sey istedigim yok. ---for myself.

Seker bile yiyemez ki -------A child who burns like a piece of paper

kagit gibi yanan cocuk. -----cannot eat even candy, anyway.

Caliyorum kapinizi -----------I knock your door,

teyze, amca, bir imza ver. --dear lady, dear sir, give me your signature

Cocuklar oldurulmesin ------so that children won't get killed,

seker de yiyebilsinler. ------so that they can eat candy.

Many many songs in which someone dies. Any favorites?

I believe the hype.

Last week-end I picked up “The Da Vinci Code,” figuring, why not? I typically read a mystery-thriller or 2 every year. My mom liked the book, Leonardo rocks the canvas, the counter-Biblical theorizing is reminiscent of ye olde Robert Graves goddess mythology -- so I jumped in.

The book is a Page Turner.

The master-narrative of a thriller is a striptease. The author always knows more than the reader, and reveals what he or she knows bit . . . by . . . tantalizing . . . bit, usually bringing the reader to the brink of revelation before veering off in another direction, the almost-revelation occurring at the moment of maximum narrative tension, at a moment of Grave Danger. Dan Brown does all of this very well, and often with the twist that the Characters at any given moment have seen more of the Naked Body of the Truth than the Readers.

As with any striptease, the ultimate revelation is bound to have instances of disappointment, and the same is true in this book. The Haunting Memory of grand-pere’s transgression, when revealed, ends up seeming dorky -- an unconvincing bit of Euro-neo-paganism. The revelation of the Chief Villain, similarly -- a moment of Dropped Disbelief.But -- and here’s the thing -- the Final Big Revelation -- that doesn’t disappoint at all. Surprisingly warm and human and even understated. Intellectually dorky, OK -- bloodlines, and the nonsense of “most direct descendants” (what would an Indirect Descendant be?) -- but as a story, it’s . . . heartwarming.

The book is full of zippy riddles and has a sense of humor and likable characters -- even the bad guys are likable, for the most part. And if I’m going to get sucked into a paranoid striptease narrative -- because the thriller is always a paranoid plot machine too, with Death lurking around every corner and behind every veil -- I’d just as soon lose myself with characters I like.

Most of the thrillers I’ve read, I don’t remember much about them afterwards. Harry Potter books too (I’ve read the first 3). I have a guess that this one might stick with me longer, because the imagery is pre-locked-in. And because I like the characters.

Fastidious reviewers have objected to Brown’s prose, even boasting of not being able to make it through the book. I noticed Brown's newspaper-ese too -- the clunkiness tripped me up once or twice -- but so what. His riffs got speed and hooks.

The rhetoric of disdain and/or apology for Brown's prose echoes now-mostly-discredited apologetic tones that middle-class strivers used to adopt when talking about liking popular music or TV or movies, and in the same publications that would never compare an Usher song unfavorably to a Schubert Lied, as used to be common. It's become bad form to denounce "bad music," but "bad prose" is still fair game.

And after all, what's not to like about zippy riddles, effective narrative striptease, and likable and sometimes humorous characters?

Pop it open!

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

i've been hearing Boston lately -- the hits of my Junior High years -- on the radio, and on a Best-Of CD i picked up for 2 bucks in a junk shop. has any other Top Band of the last 35 years had less aura? I really like the songs.

and -- how times have changed! they used to be quite Heavy Pop; now, compared to contemporary country radio, their drums are Soft and their guitars no big.

the songwriter/guitarist dresses in a T-shirt and the lead singer in a sportcoat. if one of them comes from a blue-collar background (and I have no idea of their bios, except that the songwriter was an MIT tech wiz), I'd bet it's the guy in the sportcoat.

the genre is Strut but the singer sounds like . . . a nice guy! (again -- no idea of personal lives.) Strut without Cruelty.

(Looked it up: my guess was right: Brad Delp worked in a factory until Boston made it big. And Tom Scholz was a product engineer at Polaroid. I probably read this at some point and forgot I knew it. Speaking generally, the white-collar male is concerned with looking tough, while the blue-collar male is concerned with looking good.

Please note: My criticism of blue-collar chic is not a criticism of blue-collar culture or blue-collar people. Nor is it a criticism of white-collar people for having white-collar jobs. It's a criticism of white-collar people who fetishize what they imagine blue-collar culture to be.)

ideological listening

When Big Bill Broonzy toured England in 1952, the posters showed him in work clothes and smoking a cigarette. When he appeared onstage, he wore a suit and tie.

The modern fashion of "blue collar chic" dates to the folk revival. In an upwardly mobile society, and even more when the middle class is being eroded, blue collar chic is a luxury item.

Sunday, May 21, 2006

* * * * * *

Is The Man particularly sticky? And what is this "It" that we're supposed to stick to him?

Wednesday, May 17, 2006

history of an error

In his review last October of Peter Guralnick’s biography of Sam Cooke, Robert Christgau said that while Guralnick’s earlier writing “implied an informed version of the old blues-and-country-had-a-baby theory of rock and roll,” the Cooke bio gave him “little choice but to emphasize rock and roll's more recently recognized gospel roots.”

A more accurate account would have said, “rock and roll’s recently remembered gospel roots,” because earlier accounts of the music included gospel in the story, but Christgau’s generation buried that part of the story.

In 1956, the unknown and anonymous RCA liner note writer for Elvis’s second album (which has the difficult-to-google title Elvis) included these observations about Elvis’s roots:

There has never been a great difference between rhythm and gospel songs except, of course, for the lyrical content; in fact, the latter are far more rhythmic where staging is concerned. It is essentially the fervour, the animation and boundless spirit of gospel singing that Presley admires, and which has been absorbed into his own dynamic performances. . . . Presley favours beat and ballad singers alike, . . . -- which leads to this possible answer for the ‘Why?’ of his unprecedented appeal: Elvis Presley, by combining the four fields (country, gospel, rhythm and pop) into perfect unity, is unique in music annals and experience.RCA wasn’t the only early cultural arbiter to recognize gospel’s centrality in rock and roll’s story. Jazz critic Martin Williams, writing about rock and roll for Downbeat magazine in October 1965 (collected in his book Jazz Masters in Transition 1957 - 1969), said,

(Quoted in The Penguin Book of Rock & Roll Writing.)

Williams makes this observation while discussing Petula Clark’s smash hit “Downtown,” a song that owes nothing to country, little to blues, a fair amount to (non-rocking) pop, and its rhythm to girl group and soul and, ultimately, gospel. If you prefer not to think of Petula Clark as a rock and roll singer, substitute Martha Reeves or the Ronettes. And once you start talking about Motown and Phil Spector, you’re talking about the Beatles too.

It should be fairly common knowledge by now that the first stylistic forebear of rock ’n’ roll was Negro rhythm and blues and that the second was a secularized version of Negro gospel music.

Christgau is wrong to call the recognition of gospel as central to rock’s story “recent.” It is, however, recently remembered, because for more than 30 years, the myth was, “blues had a baby,” or, “blues and country had a baby and they named it rock and roll.” I haven’t traced who first came up with the formulation, but Rolling Stone magazine was an early promulgator, Creem followed not too far behind, and prominent writers implied it heavily, like Guralnick and Greil Marcus, who in his hugely influential 1975 book Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock and Roll Music profiles 4 rock acts and two “Ancestors” -- one blues and one country.

The 1970 book The Rock Story: The Names, the Faces, the Sound that Turned On a Generation by Rolling Stone Editor Jerry Hopkins begins with the one-paragraph sentence, “The roots are in blues and country.” (The book never grabbed me, but it is notable for devoting one of its 14 chapters to the notorious groupies the Plaster Casters.)

Six years later, the blues-&-country-had-a-baby myth was so well established that writers apologized for repeating it. “Rock Revolution, From Elvis To Elton -- The Story Of Rock And Roll, By The Editors Of CREEM Magazine” begins with these sentences: "The origins of rock 'n' roll have been repeated so often it sounds like a litany. Black blues and white country music were the basis of rock 'n' roll.”

Martin Williams’s jazz criticism posits that the key to understanding jazz history is to listen to the rhythms first; that rhythmic changes lead stylistic changes. Williams was my first critical love (Nik Cohn was my 2nd, and Greil Marcus my 3rd), and rhythmcentrism still has value for considering American music history and feeling stylistic boundaries.

From a rhythm perspective, gospel is central to the rock story. By the mid-’40s, the acoustic guitar-piano-bass-drums quartet that Sister Rosetta Tharpe led was playing shuffle rock beats. Far more than blues, gospel influenced the beats of soul and girl group. Martin Williams and that unknown RCA Records staffwriter had it right: “In fact,” said the latter, gospel is “far more rhythmic” than blues.

(A whole sidelight I’m not going to go into right now: how a lot of the rhythmic funkiness of gospel and soul came from jazz players, from (again) Sister Rosetta Tharpe and her band to Motown and James Jamerson.)

To exclude gospel and pop from the story of rock is to deny basic musical experience. The blues and country gave birth to rock and roll -- what does country have to do with Little Richard? Or doo-wop? Or Phil Spector? Or the Beach Boys? Or Stax Records? Or metal? Learning the myths and then applying them to experience -- one of them has to give way.

I can only speculate as to the myth-makers’ motivations. I don’t think it’s coincidental that blues and country are both blue-collar genres: the myth-makers promoted a blue collar chic that still holds strong in rock imagery today. Robert Christgau, in his review of Guralnick’s Cooke bio, says this: “blues implies an outlaw ethos while gospel carries with it images of sustained social responsibility.” This makes sense -- and with unflattering implications for the myth-makers.

One of corollary myths of rock-mythography tells how the ’50s were dull, apolitical, and conformist. Try telling that to the veterans of the Civil Rights movement. Gospel was central to the Civil Rights movement. By eliminating gospel from the story of rock, the myth-makers cut rock off from real political roots in favor of “outlaw” rebel imagery that is politically Nowheresville. Christgau’s words resonate -- the move towards blues imagery eschews the imagery of “social responsibility.” (Of course this is an oversimplified myth as well -- plenty of people have always loved blues and gospel both.) And what is politics without social responsibility?

Dick Cheney may have something to say to that question.

Christgau observes that “blues-versus-gospel” has become a “contentious issue” in rock history, and he regrets that Guralnick missed his “opportunity to concoct a unified field theory.”

Christgau needn’t regret. Elvis embodied the unified field theory, taking in pop as well as gospel, blues, and country (as the Beatles did later), and RCA Records spelled the theory out on the back of his second album. It probably doesn’t matter why the late-’60s and ’70s rock writers turned away from the theory. But it’s always been there, and it feels right.

p.s. I have blogged about most of this before, but I wanted to gather my thoughts because of the current rock-pop discussion. In the middle of writing this post, a friend phoned and I told him I was beating my dead horses “on my flog.” My slip of the tongue made me laugh out loud.

Sunday, May 14, 2006

A number of years ago the Gates Foundation donated several million dollars to the 3-county area north and south of Seattle, from Snohomish County (where Everett is) to Pierce County (where Tacoma is). I attended the announcement by William Gates Sr., a rich lawyer who in his quasi-retirement runs the Foundation. Gates Sr. was widowed and has remarried.

It was a press conference with questions from the public. Someone asked how Bill Gates Jr. could be so generous and community-minded.

Gates Sr., blunt, terse: "He had a perfect mother."

Some young guy asked whether Gates were making this donation to housing out of a sense of guilt for playing a role in driving up real estate prices.

Gates Sr., looking the guy in the eye, steely: "No." End of that line of inquiry.

This was a man who was used to being in charge, I could tell. A definite bad ass.

The West Wing was the fantasy of a politics of integrity. But the plot of many episodes hinged on who was the tougher bad ass. Sometimes it was President Bartlett, sometimes someone bested him. That's why I wasn't convinced when Jimmy Smits won. I've missed a number of episodes, but I thought that Alan Alda generally was the tougher bad ass. But it's a Democratic Party fantasy show (where a secular pro-choice Republican can win the R nomination), and Smits was younger to boot, so it had to be him.

The final episode disappointed, but how could it not? Jimmy Smits and his team did not look psyched to be taking over the White House. Fine. Good-bye already.

Now I don't have "a show" -- one that I'm hooked into. My beloved spouse hooked me into the late Star Trek series, but we could never get in to Enterprise, and that got canned anyway. I'm still hoping for the first sit-com Star Trek spin-off, where 7 of 9 and Chakotay get married and raise a family in the suburbs. My Mother the Borg.

The 3rd tallest building in Chicago -- after the Sears & the Hancock -- is the Standard Oil Building, and in one way it’s the most striking of the three: it’s gleaming white.

Between 1984 and 1988 I wrote 6 plays which my friends and I produced, 5 short plays included in evenings of many short plays, and one full-length musical. My first 3 short plays I still like (in memory), the next one was all in rhyme and not so good (the first one had been all-rhyme too, until a long non-sequitur monologue that concluded it). My fifth play was full-length -- a musical. I haven’t read any of them in more than 15 years, but I have fond (and some not-so-fond) memories of the script of the musical, and I still sing a couple songs from it.

Then the company moved from college town Ann Arbor to Big Theater City Chicago, and I wrote one more short play before I quit writing them -- a play about the Standard Oil Building.

In the play, the architect is trying to give the building a hand job, because if it would come it would make the whole city feel good. I played the title role -- the Ghost of Electricity, which was: exhaust from burning oil. My costume was a white sheet. There was a chorus of Founding Fathers who spoke all in rhyme. I never learned anything about the building’s real-world architect, not even his name (I presume the architect was male), but in my play the planned hand-job didn’t pan out, and he was crushed. I remember the play fondly.

It was our first production in Chicago, and the evening of 6 plays or so got a generally good review, though my play got panned. The next production, the last I acted in, was the company’s 1st Chicago full-length, and it got raves, and the company’s been kicking out the jams to great critical success ever since.

A funny aftermath to my writing a play ridiculing the giant white phallus of Standard Oil on the Lake Michigan shore: once the play was over, I liked the building! So white and gleaming and phallic! So ingenuously self-parodic! And what’s so bad about a gleaming white phallus anyway!

A similar thing happened to me this week: After dragging the Rolling Stones and especially Mick Jagger through the rhetorical mud in among the thousands of words of comments to this 38-word post, I now really like the Stones again -- even Mick!

I looked for my Stones records but found that I had sold them -- “Some Girls” and an Italian import of early stuff, on vinyl. I heard a couple fave oldies on the Oldies station the other day and liked them more than ever. And today I found a really cheap used copy of a post-’60s comp called “Rewind” and dug a lot of it -- not only the rhythm section and the riffs and guitar interplay, but the melodies and -- Mick. He certainly plays the jerk often enough in his songs, but he’s an interesting and engaging jerk when he’s being jerky, and often enough he’s just an interesting guy. And good singer. I still can’t hear him without thinking of Bush, but like I said the other day, and like my good friend Jake said more clearly, that isn’t Mick’s fault. It’s just the way it is.

I looked up what a couple of my fave rockwriters had written about the Stones. It appears my wild-swinging opinions aren’t that wild: I stole them. Take it away Robert Christgau, from his excellent 1998 essay collection Grown Up All Wrong:

Jagger’s petulance offends some people, who wonder how this whiner -- a perpetual adolescent at best -- can pretend to mean the adult words he sings. But that ignores the self-confidence that coexists with it -- Jagger’s very grown-up assurance not that he’ll get what he wants, but that he has every reason to ask for it.The petulant, perpetually adolescent, entitled swagger -- that’s Bush all over. Christgau again:

Their sex was too often sexist, their expanded consciousness too often a sordid escape; their rebellion was rooted in impulse to the exclusion of all habits of sacrifice, and their relationship to fame had little to do with the responsibilities of leadership, or of allegiance. . . . All [Mick] wanted was to have his ego massaged by his public or bathed in luxurious privacy as his own whim dictated.These attributes are partly Bush, partly not, but this phrase is pure Bush: “the exclusion of all habits of sacrifice” -- as well as the complete disregard of allegiance.

And regarding my confusion over the Stones’ class imagery/personae (which Jake, again, in comments, elucidated better than I did), Christgau agrees: “due partly to their own posturing, the Stones are often perceived as working-class, and that is a major distortion.” Note: Christgau uses the typical antithesis of “working class” to “middle class”; the Stones grew up middle class, and all of their parents had to work (Watts and Wyman grew up in blue-collar households).

Christgau loves the Stones: he argues that if you say you don’t like the Stones, it “is to boast that you don’t like rock and roll” -- very much like what Jody accused me of in the comments!

More Stones commentary, from Nik Cohn’s wonderful 1969 book Rock from the Beginning, the first rock book I loved and still a fave:

In one way, though, the Rolling Stones were a breakthrough: they acted just as mean off-stage as on. Elvis, say, might have been sexual and slimy in a spotlight, but at any other time he loved his mother, his country, and his God. The Stones weren’t like that -- the looked mean, talked mean, and they were mean. They were revolt in the crudest, most vicious style possible, and they were loved like that, they caught fire. . . . Really, the Stones were quite major liberators: they stirred up a whole new mood of teen arrogance.Again, the imagery of adolescent arrogance. I don’t know about you, but that sounds like Bush to me.

Cohn is more explicit about the Stones’s class masquerading and about their misogyny than Christgau would be years later:

There were some fierce songs written, cruel, and the girls in them caught solid hell, were put down and hit and discarded like total trash. The dominant fantasy had the singer as randy working class, surly and always dissatisfied, cold, entirely ruthless, who picked up debs like dust, loved to make them break.The sex angle isn’t Bush, but “surly, cold, entirely ruthless” -- yeah man.

Cohn was 22 when he wrote his book, and he loved the Stones: “They are my favorite group. They always have been.” Is it significant that two of my favorite rock critics pick the Stones as their beloved archetypal rock band despite complete cognizance of their sexism? What does that say about rock and roll? What does it say about me that these guys are two of my favorites?

Clearly, some of the stuff is generational, and just doesn’t translate completely any more. Cohn:

[T]he Stones had a wild stage act, . . . they put on the best pop show I ever saw: final bonanza, hysterical and violent and sick but always stylized, always full of hype, and Jagger shaped up genuinely as a second Elvis, as heroic and impossible as that.I officially get off the bus here. Elvis is Elvis. None of the ‘60s white rockers come close to him as a singer, certainly not Mick.

My friend John de Roo, who hipped me to Cohn’s book when we were teen-age rock and rollers together, wrote to remind me that Mick’s persona is about sex. Cohn agrees:

And then Mick Jagger: he had lips like bumpers, red and fat and shiny, and they covered his face. He looked like an updated Elvis Presley, in fact, skinny legs and all, and he moved like him, so fast and flash he flickered. When he came on out, he went bang. He’d shake his hair all down in his eyes and dance like a whitewash James Brown; he flapped those tarpaulin lips and, grotesque, he was all sex.I’ll probably hate the Stones again some time -- or at least Mick -- but right now I’m digging the band and having a giddy Standard Oil Building relationship with Mick’s singing. Yeah, he’s misogynist and petulant; oddly, I find myself liking the petulance.

Friday, May 12, 2006

Out to dinner, our wedding anniversary -- I've been happy about it all day -- my beloved spouse is putting the 3-year-old to bed; he's going to bed late because of our luxuriously relaxed dinner, sitting at table for 2 hours, while neighbors watched him and taught him Go Fish. So cute to watch him deal a hand when we got back! "One for you, one for me, two for you, two for me, three for you, three for me, four for you, four for me, five for you, five for me, five for you -- "

Out to dinner, our wedding anniversary -- I've been happy about it all day -- my beloved spouse is putting the 3-year-old to bed; he's going to bed late because of our luxuriously relaxed dinner, sitting at table for 2 hours, while neighbors watched him and taught him Go Fish. So cute to watch him deal a hand when we got back! "One for you, one for me, two for you, two for me, three for you, three for me, four for you, four for me, five for you, five for me, five for you -- ""What comes after five?"

(He knows but has momentarily forgotten.)

"What does?"

"Ssssssssssssss . . . "

"Six!"

"OK, keep on dealing."

"Six for you, six for me, seven for you, seven for me!"

Fish.

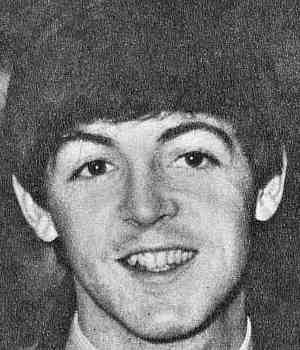

I've been arguing a lot lately, and while I'm not done, I'm too sleepy just right now to continue, and yet not to sleepy to talk about the Beatles.

I'm not sure who did it -- I think it's my friend Terry's handwriting, and his sense of humor -- but somebody left alternate lyrics in my Beatles songbook.

Michel Foucault

You French intellectual so-and-so

Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault

I don't read you but my friends don't know

My friends don't know

I read you, I read you , I read you

But I don't understand . . .

[the manuscript breaks off at this point.]

My friend Jay recently sent me a CD-R of 10 versions of "Michelle," clocking in just under 30 minutes. The Beatles' sweet version starts things off. Other highlights: Count Basie's melancholy take, a lovely arrangement on classical guitar by Manuel Barrueco (sp?), the late TV-soundtrack writer and jazz arranger and saxophonist Oliver Nelson's mod TV-jazz trot, and a Cu-Bop romp by a jazzy Latin band led by Willie Bobo. Most of the versions are instrumental; Willie Bobo's boiled-down lyrics consists of 3 words, sung by a group of men: "Michelle, ma belle" -- it cuts to the chase; you don't really miss the rest (even though the words do go together well -- and cleverly).

Paul sounds so sweet and wistfully impossible when he sings, "I love you" -- he's in love with the idea of love as much as with the woman; he knows it'll never last and he's content with the transitory nature of existence -- at least, he is when he's flirting. Without his voice, though, it's a melancholy tune. The sweetness of flirting, the melancholy of time's fleetingness.

Thursday, May 11, 2006

what grabbed my ear today

This morning, driving to work, the local community college "world of music and ideas" station: Rahsaan Roland Kirk, live, "Serenade to a Cuckoo." Virtuoso on many instruments, always an exciting bandleader, and man that guy could write catchy tunes.

After work, driving home, CD from the library: ELO's greatest hits. Love the string parts, the catchy tunes, the sheen-y but still warm '70s sound, the elaborate yet catchy and concise tunes, and -- what a chameleon singer Jeff Lynne is! I noticed it when catching "Concert for George" on PBS some months ago -- for the Traveling Wilbury numbers, Lynne sang the Orbison parts AND the Dylan parts. And sounded great, not imitative, but right, for both. He had some witty songs in ELO too, and I love the band's name -- all the words modifying each other -- Electric Orchestra, Light Orchestra (as opposed to seeeerious), Electric Light -- clever.

Rented "Gold Diggers of 1933" from the video store, "a video with singing and dancing" that the kid can watch while I'm cooking -- one of my all-time favorite movies, starting off with Ginger Rogers dressed lasciviously with large coins barely covering her bareness, singing "We're in the Money," first regular, then in pig-Latin -- and the movie doesn't go downhill from there. Choreography by Busby Berkeley. Songs by Warren & Dubin -- Warren such a great songwriter (the music) & Dubin an excellent lyricist). That opening number -- wow -- such a peppy cheerful tune, and the words of the bridge:

We never see the headlinesBecause -- "we're in the money." The Depression.

about breadlines

today,

and when we see the landlord

we can look that guy

straight in the eye

And then tonight, my beloved spouse & I spontaneously got a babysitter and went to an open mic. I brought my guitar but got there too late to sign up. Heard an accomplished & energetic guitarist who in two songs went from Malagasy-style to echo-ambient to white-hippie-jam-style funk to hippie bluegrass, and all done pleasingly and energetically. And heard Ali Marcus play rhythm guitar and sing nice alto harmony with another woman singing lead above her, an old spiritual, "I Am a Poor Wayfaring Stranger" -- really nice harmonies, always good to hear.

Tuesday, May 09, 2006

For the record: Charlie Watts does rock.

Nothing to say but it’s OK. Good evening.

Monday, May 08, 2006

* * * *

My beloved spouse and I are putting together paperwork to adopt Child Number 2. We have to get police records and court records from any arrests. My wife has gone to the clink four times for civil disobedience; once was enough for me, with the added bonus that it was an unplanned mass demonstration. I remembered the event and the general time --

summer 1984, San Francisco, during the Democratic National Convention -- but I googled to get closer to the date. I only found one article, from 2 years ago, at the web-mag Alexander Cockburn edits with Jeffrey St. Clair. Interesting to read, but I remember things quite differently!

Writer Ron Jacobs -- who was also there -- remembers the the events starting with a massive arrest of a civilly disobedient demonstration -- close to 400 arrests at guerrilla theater events and sit-ins. I wasn't at the original arrests (and neither was Jacobs), but I'm pretty sure that's not how it happened.

Every day during Convention Week an anarchist group gave a guided tour of the financial district that went something like this, repeated over and over:

"This is Building A, Corporation B has offices here, they build Weapon System C and give D amount of money to the Republican Party and E amount of money to the Democratic Party."

I went on the tour the day before the mass arrests. Other than a few "tourists" banging on windows, that was all there was to it -- a purely informational walk. Well, that's not how the police saw it. As the few dozen of us walked around, we had serious accompaniment. First, the foot cops. Then, a while later, the motorcycle cops joined us. Then, ominously, the horse cops. But nothing happened.

A day or 2 later, someone organized a free concert of punk bands in a parking lot near the convention. I don't remember most of the bands, but Millions of Dead Cops (or MDC, as they preferred to be called at that time) had the sweetest, friendliest demeanor of any band I have ever seen*, and the Dead Kennedys, who headlined, were magnificent. A bunch of other bands played, which I don't remember. What I do remember was being 21 years old and feeling too old to slam dance! (I was so much older then. I'm younger than that now.)

And, I remember, between bands, a stentorian male leftist taking the microphone between bands and shouting. " THE SAN FRANCISCO POLICE HAS ILLEGALLY ARRESTED THE ANARCHIST TOUR OF THE FINANCIAL DISTRICT. AFTER THE DEAD KENNEDYS GET DONE PLAYING, WE'RE GOING TO MARCH DOWN TO THE HALL OF JUSTICE AND DEMAND THAT THEY BE SET FREE!"

That sounded like fun, so after the Dead Kennedys played my pals and I joined a few thousand people and sat in the street outside the Hall of Justice. The cops came and divided the group in two; my friends and I were among those that got arrested. We were sitting, and cops came and handcuffed us and took us into buses one by one. I was nervous! While we were waiting, to lighten the mood, I started chanting, "Lions and tigers and bears, oh my," and when my cop came to take me away, I sang to him, "It had to be you / It had to be you." He didn't laugh.

They let everyone go in the middle of the night who wanted to be let go, but my friend and I had no place to go and I was catching a cold and didn't want to sleep in the park, so we spent the night in a jail cell with a bunch of other guys from the latter mass arrest. The first mass arrest had busted 89 people, I think, and the 2nd one brought in 250 or so more.

Only one man from the first arrest was in our cell, a vacationing high school teacher from New York who hadn't even been part of the anarchist tour but just happened to be standing next to them when the arrests happened. "They would have let us all go by now if you ass-holes hadn't come and demanded that they let us go," he said to us. Bitterly. They let us all go in the morning.

I got back to Michigan a week or so later, and I remember being utterly flabbergasted that nobody had heard about 330-some people being arrested in peaceful protests in one day in San Francisco. "Slicker and much more effective than Pravda," I thought to myself, "simply not to report the news you don't want reported."* *

* What made MDC so sweet: at one point, a skinny mohawked fan grabbed the mic from the lead singer so he could sing the song. The singer, like the coolest big brother in the world (not like Orwell's) put one arm around the kid and acted out the song with his free hand while he mouthed the words off-mic -- he was so happy. Later in the set, an African American man got on stage and started improvising a blues. The band fell in behind him and the lead singer got a bunch of fans onstage and they all danced around in a circle as this complete stranger stole their show -- except you can't steal something that someone lets you have.

* * A couple years after the WTO protests of 1999 I met one of the King County Labor Council honchos who helped organize it. He estimated 40,000 to 50,000 people on the big day. The Labor Council had hired an aerial photographer to document that massiveness of the gathering, but the Federal Aviation Administration had banned all flights above Seattle on the day. Visual documentation would only be fragmentary and piecemeal.

"Hey, hey, you, you get offa my cloud!"

"Hey, hey, you, you get offa my cloud!"“The Stones don't rock. Or, they rock in the way that Disneyland is magical.”

Sunday, May 07, 2006

Incipient teen-age-boy-dom in the 3-year-old.

The other afternoon, driving home from errands, I switch the radio to a comedy spot that comes on every weekday at 5:20. Two guys are talking about the "Girls Gone Wild" videos, they're not funny, I switch the station.

The 3-year-old says, "I want to hear about the girls lifting up their shirts."

And: "Can we watch the video of the girls lifting up their shirts?"

We pull into our parking spot behind the house, off the alley, and our good friend J.G. has his old green sports car out of the garage for the yearly airing.

The 3-year-old says, "I want to ride in J.G.'s green car!"

* * * *

In an interesting post on continuities and discontinuities between Berlin and Gershwin, Jody Rosen mentions a parallel switch in pop singing style, from “the schmaltz-drenched Jewish belters of the 1910s and 20s (Jolson, Sophie Tucker, Fanny Brice)” to “middle-American crooners (Crosby, Astaire, Rudy Vallé, Russ Columbo, et al.) whose singing communicated post-ethnic ease and reserve.”

This quote illuminates at once my Streisand problem and Carl Wilson’s Celine Dion problem: Streisand and Celine are both schmaltz-drenched belters who lack post-ethnic ease and reserve. (Carl is writing a book about Celine.)

As it happens, I don’t have a problem with Streisand, and that’s my problem: as a fan of rock and blues and jazz and folk, I’m supposed to have a problem with her. I happen to love her excessive emotionality; though I will confess to having been surprised when one day around age 30 I realized I loved her music, having heard it all my life (Mom’s a big fan), and, as a good rocker etc., having effected not to like it.

I remember reading some jazz critic -- Martin Williams? Gary Giddins? (I don’t remember) -- comparing Judy Garland to Al Jolson. Judy was one of Streisand’s main influences (as Streisand is one of Celine’s); Jody’s insight puts it all into perspective.

I love Astaire and Vallee and Crosby too -- don’t get me wrong.

This pertains to the paper I proposed for last year’s EMP Pop Conference, which was on the theme of persona in popular music. My proposal was called, “Barbra Streisand as Bob Dylan’s Double.” Here it is:

Bob Dylan’s counter-assimilationist persona is a turning-point in the history of showbiz. His Beat-bohemian spin on the left-proletarian voices of Sandburg and Guthrie inspired musician-personas as varied as McGuinn’s detached hipster, Fogerty’s bayou everyman, Tom Waits’s Beatnik boozer street visionary, and Gillian Welch’s stoic mountain gal. The aggressively alienated punk stances of R. Hell, J. Rotten & Co. amplified Dylan’s refusal to assimilate while giving it a different look.

Even more original than Dylan’s fusion of bohemian Beat and lefty prole was his fusion of outsider and star. Before Dylan, stardom was about assimilation. Frederick Austerlitz, Frances Gumm, and others had enjoyed huge careers after adopting more Anglo or more glamorous names. In showbiz mythology, farm girls and street kids could end up Puttin’ on the Ritz through grit and moxie – and by adopting upper class manners. Dylan fronted as lower class than his actual upbringing.

Despite his path-breaking downwardly mobile persona, young Bob Zimmerman followed showbiz tradition by effacing his Jewish background, just as Moses Horwitz disappeared his Jewish surname and became Moe Howard. Barbra Streisand’s persona stands in contrast. Streisand could be Dylan’s double: 11 months his junior, equally precocious early success, equal longevity and iconicity, proudly showbiz where Dylan wasn’t, proudly Jewish where Dylan was ethnically ambiguous. In a post-rock world, we can see Streisand’s fusion of Jewishness and glamour as almost as bold and oddly more authentic than Dylan’s fusion of counter-assimilation and commerce: She really was Jewish and showbiz; Dylan only pretended not to be.

(In case you don’t know, Frederick Austerlitz is Fred Astaire [Jody’s comment about post-ethnicity is dead on]; Frances Gumm is Judy Garland; and Irving Berlin [ne Israel Baline] wrote “Puttin’ on the Ritz,” and Astaire introduced it. My proposal was not accepted.

The Streisand / Dylan connection continues down mythically to this day: During the 2004 Presidential campaign, liberal journalist and scholar Eric Alterman repeated a snarky comment someone made questioning Streisand’s liberal bona fides, accusing her on no basis whatsoever of being a secret Republican out of economic self-interest, this despite the fact that Streisand has raised I don’t know how many hundreds of thousands of dollars for the Democrats for more than 30 years. The contrast struck me: Dylan remains a liberal/progressive icon, at least among some, despite his vast wealth and his avowed apoliticism: not only does he not raise money for liberals, he makes fun of people who vote.)

Saturday, May 06, 2006

Lovely party at Bob the drummer's house tonight, in honor of his wife's birthday. I brought my guitar but didn't get it out. Mr. Jumping Chocolate Pudding fell in with 2 brothers we hadn't met before, a boy a month older than him and a boy 3 years older. It was great to come into the living room after being outside and see my son leading a sing-along of "The itsy bitsy spider" and "The alphabet song" while playing toy snare drum. A little while later Skip played fiddle tunes and Mr. Jumping Chocolate Pudding accompanied him with quiet fills on the toy snare. Skip and I chatted about organizing house concerts for our music -- preferable to clubs, which start so freaking late and lack chairs (which is fine for dance bands), or even cafes, where half the people there aren't paying attention. Hopefully this summer.

I remixed 3 songs on the band's album the other night, and re-did a vocal part on a 4th song. Unfortunately re-doing the vocal part at the beginning of the song somehow threw out of balance a vocal part at the end of the song. I have no idea how that happened, but now I want to go back and re-fix that vocal part at the end that I didn't want changed. Happy with the re-recorded vocal part and the re-mixes, but good golly I want to be done. I may even keep the out-of-balance conclusion to that song, I'm so ready to be finished.

Carl Wilson had a post on band names the other day, which got me thinking -- I wish I could forego band names. I seriously thought about naming my band "John Shaw and the [something something]," which doesn't really solve the problem -- there's still that name at the end (leading contenders were "John Shaw and His Issues" and "John Shaw and His Weapons of Mass Destruction," which Mac suggested and I hated -- I didn't want to be invaded!). It wouldn't be right just to call the band "John Shaw," because even though I convene the band, write the songs, book the gigs, pay for the recording, and have final say on arrangements, we do arrange the songs together (I never would have thought of half of Bob's drum parts), and four of us share lead vocal duties. The band's name is Ruby Thicket. But now I'm tempted simply to omit the band credit. Keep the songwriting credits & recording credits & musician credits, but have it be more like a movie -- "It Happened One Night" rather than "Frank Capra's 'It Happened One Night.' " That might be interesting.

(While Googling to see if I'd written about these discarded band names before, I learned that a professional trumpeter and lute player with my name invented the tuning fork (scroll down to 1711), which is funny because I don’t like electronic tuners and prefer to tune my guitar by ear.)

I'm dreaming of the next record, and the next one after that. Definitely want to keep the band together, but have different guests on different songs. Maybe get my friend Jake to play some lead guitar; would love to get my friend Joe to sing lead on part of a song and maybe play his bodhran; hopefully bring in a few other players, diversify the pallette.

By the way, Carl's paper at the EMP Pop Conference last weekend was absolutely aces, a really thoughtful, deeply felt exploration of what his revulsion for Celine Dion's music reveals about his feelings about identity and social class. He's writing a book about it, which I'm eager for.

A few thoughts, quickly:

* I missed most of the conference, mostly because as a musical observer I'm a volunteer, and I couldn't justify taking more time away from my job and my family. I would have loved to have caught more, but I also love my life the way it is, and was simply happy to have heard what I heard.

* Alex Ross's hour-and-a-half speed-skate through 20th century classical music history was entertaining and charming -- great to hear so many clips, many from pieces I know, many from pieces I knew of but hadn't heard, a few from pieces & people I hadn't heard of. Alex's love for and consummate knowledge of the music always comes through. Was happy to be able to accost him afterwards and shake his hand -- we had corresponded before; now he's post-virtual to me.

* Jody Rosen and I had actually snail-mailed each other and exchanged CD-R's, so it was great to meet him in person too, though I missed his talk.

* Happy also to accost Franklin Bruno and shake his hand (another email correspondent), though I missed his talk as well.

* Shook the hands of Douglas Wolk (another occasional correspondent) and Michaelangelo Matos (with whose blog this one is mutually linked), but they were both in hurries and I didn't have a chance to introduce myself but merely paid them compliments, which was nice to be able to do. Matos's talk was largely autobiographical and deeply moving (and here is the complete text), and Douglas's apparently got a standing ovation, but I missed it.

* Wanted to meet Daphne Carr (another occasional correspondent) but didn't get the chance; missed her talk, but read it online and enjoyed it.

* Briefly said hello to popcrit power couple Ann Powers (whose talk I missed) and Eric Weisbard (whose talk on the Isley Brothers I really liked).

* Elijah Wald's talk on Louis Armstrong's love for Guy Lombardo reminded me that the macho critical denigration of sentimental sweet music pre-dates rock criticism: the great jazz critic Martin Williams (the music writer who has probably taught me more about listening than any other) hated Guy Lombardo. I had long noticed similarities in timbre between Lombardo and Duke Ellington in his "sweet" mode; it was nice to hear someone make the connection publicly. (The dichotomy in the early recorded jazz era, '20s through '40s, wasn't hot vs. cool, it was hot vs. sweet. I think we should bring "sweet" back into the critical vocabulary -- it really gets at what a lot of music is trying to do.)

* New Orleans drummer and professional scholar Bruce Boyd Raeburn (who is white) gave a masterfully detailed talk on the racial/ethnic category "creole" in New Orleans history, culture, and music, accompanied by great slides. Two slides stuck out for me: King Oliver's guitarist in 1931 had a double-neck guitar, which totally piqued my curiosity -- what was the 2nd neck used for, and how was it tuned? And a 1915 shot of Jelly Roll Morton doing vaudeville in blackface really altered my conception of Morton. I had thought of him as a pompous and pretentious person; this shot reminded me: In addition to being a great musician, he was a professional entertainer, and one who, it's too easy for me to forget, had to endure the insults of a deeply racist society.

I was happy to hear that EMP will host the Pop Conference again next year.

I always simply assumed that one of my favorite political bloggers, Digby, is a man. I pictured him as a casual, intense, 50-ish, tall, sandy blonde screenwriter. But then a couple weeks ago another of my favorite political bloggers, Steve Gilliard, referred to “Digby” as “she.”

Steve would have reason to know.

Why would I think she was a he? Now, when I read Digby, instead of imagining a laid-back, warm, sarcastic male voice, I hear a warmer, still sarcastic female voice.

It appears that “male” is my default perception. What’s up with that?

And: I imagine sarcastic, snarky bloggers as short. What’s that about?

“Unpacking” my “baggage.” Now I can throw it around the room! Make a big enough pile, and I can jump in it, like raked leaves!

Thursday, May 04, 2006

the history of my love for smooth R&B

I was waiting tables in a downtown Chicago restaurant during part of the hit reign of Anita Baker's "Rapture." We listened to R&B pop radio. Half the wait staff was African American, as was the head cook. None of us at the restaurant was remotely close to rich (why would be working at a mediocre lunchspot otherwise?); I'd bet that none of us had been graduated from college (I was a drop-out). We all dug Anita Baker. Her vocal timbre for one phrase of No One in the World reminded me of the sainted George Jones; I bought the album on cassette and still think it's great: her voice, the melodies, the depth and detail of the arrangements, the marriage of words & music in rich emotion.

My job before that was on the Chicago side of Howard Street, in the Rogers Park neighborhood on the Evanston border, doing clerical work for a mail-order pornography business. The publication consisted classified ads for escort services with naked pictures attached; two tough white women owned the business; sales were drummed up by 4 or 5 female phone workers, all but one of them African American, who sugar-talked potential customers. One of my co-workers commuted an hour and a half each way by bus from the south side. The most successful phone worker was a very sweet, quite burly white man in drag. I was the only male-identified person there.

Smooth R&B radio was what we listened to. The Whispers had a beautiful hit during my brief tenure there, It Just Gets Better With Time.

Wednesday, May 03, 2006

Grouchy from lack of sleep lately; hence, little posting, which I regret, because, whether you’ve missed me or not, I’ve missed you.

What I caught of the EMP Pop Conference last week-end was swell and more than swell; comments to come.

I’ve been listening the last few days to Mariah Carey’s MTV Unplugged Live EP. The crazy high notes she hits are dramatic like Duke Ellington’s crazy-high-note trumpeter Cat Anderson could be, except Mariah is her own Cat Anderson, and her intonation is better. She dollops on the melisma with more gusto than the ‘50s and ‘60s soul stars, but I dig her virtuosity as I dig John Coltrane’s, who faced similar criticism. But not only are

Carey’s range and speed stunning, I also love her timbre. A beautiful baseline tone with a subtle variety of effects. Enjoying getting to know her stuff.

* * * *

Also been listening to another excessive melismatic, Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Tharpe belongs in the center of the history of rock. Among her accomplishments:

1. Perhaps the first rock-and-roll guitarist, having played distorted bluesy electric guitar leads as early as 1941 with Lucky Millinder’s swinging big band. Chuck Berry swiped some of her licks. Howling Wolf’s guitarist Hubert Sumlin may have too.

2. An early codifier of the classic soul-rock line-up of electric guitar, organ, piano, bass, and drums.

3. An influential singer, from Elvis to today’s melisma queens.

4. The biggest star in gospel for most of her career.

5. A solid solo-acoustic blues-boogie practitioner.

6. An astonishing joy to listen to.

When I bought her bargain (though repetitious) 4-disc box set The Original Soul Sister a few years ago, I bumped into Kurt Reighley, a local rock critic with whom I am acquainted, who asked me, “Why wasn’t she in Rolling Stone magazine’s list of 100 greatest guitarist?”

Anyway, I listened to her 1956 masterpiece, Gospel Train, yesterday, and I sobbed from the beginning to the end of her song about entering heaven after “crossing to that other shore,” the spooky, hushed, mournful “I Shall Know Him,” which concludes, “by the prints of the nails in His hands.” Her Jesus suffered greatly.

* * * *

Also been listening to Duke Ellington’s off-the-cuff 1959 masterpiece Blues in Orbit. A cornucopia of instrumental blues moods, from jaunty to indigo melancholy, with his matchless sense of orchestral color. A fairly typical mix of great standards from his own songbook and brand new gems. Can’t ever hear too much Duke.

* * * *

Conversation from last week:

The kid: "We went to Broadway."

Me: "Were the neon lights bright on Broadway?"

The kid: "What'd you say? Something silly of course."

My beloved spouse: "He's got your number!"

* * * *

Bonus track: Looking for something I wrote before about Sister Rosetta Tharpe, I came across this review I wrote in January 2004 of the box set and the reissue of “Gospel Train,” both of which had come out not too long before. I was going to pitch it to the “Village Voice,” but decided to start this blog instead. A record review I never tried to publish:

ROLLING STONES AWAY WITH JESUS

review of GOSPEL TRAIN and THE ORIGINAL SOUL SISTER by Sister Rosetta Tharpe

A recent boomlet of interest in virtuoso gospel belter Sister Rosetta Tharpe has brought the reissue of her 1956 album “Gospel Train” along with a 4-disc box set, “The Original Soul Sister.” “Soul Sister” shows off Tharpe’s stylistic breadth, from her first late ‘30s solo-gal-with-a-guitar recordings, through early ‘40s secular and sacred sides with a big band, to her first big gospel hits with a small acoustic R&B group in the mid-’40s. Her first records at age 23 in 1938 show Tharpe to have been, like her contemporaries Big Bill Broonzy and Robert Johnson, an early exponent of the thunka-thunka blues boogie guitar rhythm that foreshadowed rock and roll. Tharpe’s sprightly vocal tone suits the handful of secular songs like that hymn to multiple orgasm, “Four or Five Times,” but sounds incongruously joyous when banning “smokers” and “wankers” from Glory. When the songs leave moralizing behind and embrace visionary ecstasy or uncanny Biblical narrative (or, secularly, lust), the music conveys the ecstasy and does justice to the uncanny (and the lust).

“Gospel Train” omits the finger-pointing and is all about ecstasy and the uncanny. When she’s testifying-about rather than preaching-at, Tharpe confronts the life-ultimate questions of meaning, death, multiplicity, and consciousness with a resonantly fervent brew of joy, awe, and existential freak-out. The object of her freak-out is Jesus, but “Gospel Train” puts him in visionary, personal terms. “I’m going to Jesus,” Tharpe chants at one point, and, at another, “there are days I like to be all alone with Christ my Lord.” Evidently her Jesus is a physically existent dude of her personal acquaintance. And the band cooks hot. The organist, pianist, and 2nd guitarist improvise dense soul-blues obligattos, while the swing-jazz-refugee bassist and drummer lay down tight proto-soul beats. It’s a tougher sound than anything on “Soul Sister.”

Layered on top like a beautifully weird-ass frosting are Tharpe’s electric guitar freak-outs, which on “Gospel Train” play like the love child of Hubert Sumlin and Chuck Berry jamming with Aretha Franklin’s 1968 band. But “love child” is anachronistic because “Soul Sister” shows that as early as 1941 Tharpe was playing dirty distorted electric solos that sting and skronk with speedy triplet runs, bluesy bent notes, slashing slides up the neck, winking vibrato, Chuck-ling double-string licks, and a driving, syncopated rhythm with abrupt, ear-grabbing phrasing.

What W.E.B. DuBois capitalized as the Frenzy and the Music of the black American church can sound erotically carnal to people raised on rock and roll, especially since mainstream American religion is a meditative descendant of Puritanism. But the church wasn’t always button-down and gray flannel. In the Acts of the Apostles the first Christians pray so hard that buildings shake. Gospel honors that tradition, and songs about the resurrection of bodies and of knowing Jesus “by the prints of the nails in His hands” reveal Tharpe’s Christianity to be doctrinally as well as musically carnal. If you have ears for rock and soul history, Tharpe’s music testifies that upon this church we have built our rock. And “Gospel Train” can make an agnostic devotee of Charlie Watts wonder whether the original “rolling stone” wasn’t necessitated by the Resurrection after all.