Archives

- 01/01/2004 - 02/01/2004

- 02/01/2004 - 03/01/2004

- 03/01/2004 - 04/01/2004

- 04/01/2004 - 05/01/2004

- 05/01/2004 - 06/01/2004

- 06/01/2004 - 07/01/2004

- 07/01/2004 - 08/01/2004

- 08/01/2004 - 09/01/2004

- 09/01/2004 - 10/01/2004

- 10/01/2004 - 11/01/2004

- 11/01/2004 - 12/01/2004

- 12/01/2004 - 01/01/2005

- 01/01/2005 - 02/01/2005

- 02/01/2005 - 03/01/2005

- 03/01/2005 - 04/01/2005

- 04/01/2005 - 05/01/2005

- 05/01/2005 - 06/01/2005

- 06/01/2005 - 07/01/2005

- 07/01/2005 - 08/01/2005

- 08/01/2005 - 09/01/2005

- 09/01/2005 - 10/01/2005

- 10/01/2005 - 11/01/2005

- 11/01/2005 - 12/01/2005

- 12/01/2005 - 01/01/2006

- 01/01/2006 - 02/01/2006

- 02/01/2006 - 03/01/2006

- 03/01/2006 - 04/01/2006

- 04/01/2006 - 05/01/2006

- 05/01/2006 - 06/01/2006

- 06/01/2006 - 07/01/2006

- 07/01/2006 - 08/01/2006

- 08/01/2006 - 09/01/2006

- 09/01/2006 - 10/01/2006

- 10/01/2006 - 11/01/2006

- 11/01/2006 - 12/01/2006

- 12/01/2006 - 01/01/2007

- 01/01/2007 - 02/01/2007

- 02/01/2007 - 03/01/2007

- 03/01/2007 - 04/01/2007

- 04/01/2007 - 05/01/2007

- 05/01/2007 - 06/01/2007

- 06/01/2007 - 07/01/2007

- 07/01/2007 - 08/01/2007

- 08/01/2007 - 09/01/2007

- 09/01/2007 - 10/01/2007

- 10/01/2007 - 11/01/2007

- 11/01/2007 - 12/01/2007

- 12/01/2007 - 01/01/2008

- 01/01/2008 - 02/01/2008

- 02/01/2008 - 03/01/2008

- 03/01/2008 - 04/01/2008

- 04/01/2008 - 05/01/2008

- 05/01/2008 - 06/01/2008

- 06/01/2008 - 07/01/2008

- 07/01/2008 - 08/01/2008

- 08/01/2008 - 09/01/2008

- 09/01/2008 - 10/01/2008

- 11/01/2008 - 12/01/2008

- 01/01/2009 - 02/01/2009

- 04/01/2009 - 05/01/2009

- 07/01/2009 - 08/01/2009

- 09/01/2009 - 10/01/2009

- 10/01/2009 - 11/01/2009

- 11/01/2009 - 12/01/2009

- 12/01/2009 - 01/01/2010

- 03/01/2010 - 04/01/2010

Utopian Turtletop. Monsieur Croche's Bête Noire. Contact: turtletop [at] hotmail [dot] com

Wednesday, January 24, 2007

Been reading books about music; in the middle of some terrific ones, for some reason I put them down to read others more lightweight and not as terrific. Finished one of the latter today; last week finished two and jotted some notes on them. Here are the notes.

Been reading books about music; in the middle of some terrific ones, for some reason I put them down to read others more lightweight and not as terrific. Finished one of the latter today; last week finished two and jotted some notes on them. Here are the notes.* * *

Read Erik Davis’s 33 1/3 book on the album known as Led Zeppelin IV (which is officially titled something as un-typable as what Prince used to be styled when he was the Artist Formerly Known as Prince), a wacky and erudite exploration of Zep’s relationship with occult studies, practices, and imagery. A quick zip of a blast to read, Davis pulls off the improbable feat of a making a lyric-centric reading of Zeppelin fascinating and compelling.

Now, this, of course, is way off the mark. Not that the lyrics are uninteresting (though I’ve blasted them before, in pixels, on this blog), but that Zep’s downgrading of lyrics was one of their big breakthroughs. It’s true that “to be a rock and not to roll” is more than a merely clever line and does have Parmenidean overtones (Davis does not mention him but his discussion made me notice the line’s link to Parmenides), but always, what matters most with Zep is the SOUND. And, to be fair, Davis has decent respect for the magic of music, and Zep’s musical prowess.

But he repeats one of the ignorant biases of old-line rockcrit: He disses Bonham. “Ham-fisted,” he quotes Christgau, in one of Christgau’s dumbest lines. Davis mitigates this by quoting a more musically-attuned critic, the late, lamented, and acute Robert Palmer: Zep and Bonham “swing like mad.” Make that, swung. First, swing is Everything, even more everything than timbre is everything. Second, Bonham could play lightly as well as thunderously swingingly – dig his 5/4 lilt on “Four Sticks.” In my mod-punk-jazz youth, I dissed Zep too, but it was a case of denial. I always loved them, but my allegiance to skinny ties made me deny them. A drummer friend of mine in high school called Bonham the greatest. I thought he was nuts. Now I don’t.

Davis’s book has the virtue of sending me back to the record, and it really is one of the peaks of AOR. Not a bad tune on the disc; all of them but “Going to California” strike me as inimitable masterpieces. (“Going to California” might strike me that way too, but for its closeness to the more florid and compelling “Battle of Evermore.”)

And, what nobody mentions, the record is pure pop. Davis is good on Page & Jones’s craftiness, but he misses one of the keys to the record: Bonham lays out a LOT. Page was a master of layering guitars, but the band as a whole had a tremendous knack for dramatic pop arranging, where the drums lay out for the climactic hook. “Been a long lonely lonely lonely lonely lonely lonely time.” Really exemplary throughout, and I bet their arranging scores extremely high on those computer programs that judge a record’s pop-potential.

A running joke/theme of the book calls the songs’ narrator “Percy,” after the British slang for penis and in echo of the Arthurian knight Parsifal, the holy fool. Davis’s joke: Plant’s persona is the penis as holy fool. Witty, but too condescending to bear repetition at book length. I’ve dissed Plant’s lyrics too, but usually I can’t make them out; usually the music invites me not to make them out; and musically, sonically, rockingly – that’s brilliant. When I can make out his lyrics, I’m growing to like them. I’ve repented my condescension to Plant’s poesy. “Stairway to Heaven” engages me (“bustle in your hedgerow” does sound incongruously silly; the Tolkien allusions in other songs do too) and he has many memorable lines.

If you’re interested in Page’s relationship to occult theorist Aleister Crowley, I recommend the book. I’ve never read much about Zep; this makes me want to read more by Davis (and to hear more Zep – still have never heard some of their stuff).

* * * * * * *

Ken Emerson’s breezy Always Magic in the Air: The Bomp and Brilliance of the Brill Building Era reads like a cheery, 200-some page magazine article, with less cynicism than most magazines and less weight than the best magazines too. Lots of bio-detail about the Seven Big Songwriting teams of the Brill era:

Goffin & King

Bacharach & David

Leiber & Stoller

Mann & Weil

Barry & Greenwich

Pomus & Schuman

Sedaka & Greenfield.

And lots about publisher / impresario Don Kirschner, and Phil Spector, and the gang.

But a few days later, I don’t remember much of it. But I enjoyed every bit of it, even Emerson’s cheery MOR sensibility, dropping his opinions just where several decades of rockcrit consensus would lead you to expect he would drop them – Monkees, untalented (I disagree); Bacharach, brilliant but schlocky when not hardened up by the influence of Black styles (disagree about the shlock); Black style, emotive (umm . . . ); Leiber & Stoller, brilliant (agreed); and so on.

Correction: I did remember a bit about the Monkees history that I hadn’t known: When the Monkees demanded their creative freedom, they only won it because the producer backed them up, and the producer was the conglomerate boss’s son. Emerson botches the story and the history there – he misses the salient fact that after the Monkees grabbed the brass banana, they continued to work with Boyce & Hart and Goffin & King. Nothing much changed.

And, I remember stuff about all of the songwriters that I hadn’t known. It’s a nice book. Recommended to Brill Building hounds who don’t know the history already, which I didn’t, much, though I’ve always adored the music; we covered “He’s So Fine” in high school, straight up, with a female friend singing lead; how I loved singing that “Doo lang doo lang doo lang”; a fond memory.

* * * * * * * * * *

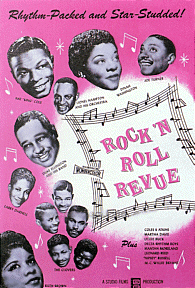

In 1955, the date of the movie poster above, Rock 'N Roll hadn't calcified yet. Duke Ellington, Dinah Washington, Nat King Cole: rock 'n rollers.

Elvis and the Beatles and the Beach Boys and James Brown and Ray Charles agreed: They sang Broadway and Tin Pan Alley and jazz tunes as well as R&B and country.

Dylan and the Rolling Stones disagreed. They disdained that stuff. (Wait, no; not that simple; the Stones covered a song associated with Nat King Cole, "Route 66"; but that was anomalous.)

Dylan and the Stones won the argument. (And Pete Seeger would have approved, at least back then.) No genteel music, please.

Funny: jazz used to represent un-genteel.

(Borrowing the genteel / vulgar distinction from a terrific essay by John Rockwell on Burl Ives.)

Now rock is genteel, and for decades, rock critics have used the snobby rhetoric of gentility to mock the old genteel style: "shlocky," "over-emotional," "kitsch."

Ah well, life is funny. What can a poor boy do?

Comments:

"Ham-fisted" implies heavy-handed gracelessness. When Christgau also called Bonham's drumming "dumb," as in, "stupid," which he did, the implication is obviously intended. Which is stupid. Even when he said he loved Bonham's drumming, he still called it dumb.

It's been fashionable among critics to condescend to musicians, since Nik Cohn at least. It's a bad fashion. Knowing how to make great music might not mean you aced the S.A.T.'s, but the S.A.T.'s are a very limited measure of intelligence. It's embarrassing when people touting their own smartness don't know that.

Post a Comment

It's been fashionable among critics to condescend to musicians, since Nik Cohn at least. It's a bad fashion. Knowing how to make great music might not mean you aced the S.A.T.'s, but the S.A.T.'s are a very limited measure of intelligence. It's embarrassing when people touting their own smartness don't know that.