Archives

- 01/01/2004 - 02/01/2004

- 02/01/2004 - 03/01/2004

- 03/01/2004 - 04/01/2004

- 04/01/2004 - 05/01/2004

- 05/01/2004 - 06/01/2004

- 06/01/2004 - 07/01/2004

- 07/01/2004 - 08/01/2004

- 08/01/2004 - 09/01/2004

- 09/01/2004 - 10/01/2004

- 10/01/2004 - 11/01/2004

- 11/01/2004 - 12/01/2004

- 12/01/2004 - 01/01/2005

- 01/01/2005 - 02/01/2005

- 02/01/2005 - 03/01/2005

- 03/01/2005 - 04/01/2005

- 04/01/2005 - 05/01/2005

- 05/01/2005 - 06/01/2005

- 06/01/2005 - 07/01/2005

- 07/01/2005 - 08/01/2005

- 08/01/2005 - 09/01/2005

- 09/01/2005 - 10/01/2005

- 10/01/2005 - 11/01/2005

- 11/01/2005 - 12/01/2005

- 12/01/2005 - 01/01/2006

- 01/01/2006 - 02/01/2006

- 02/01/2006 - 03/01/2006

- 03/01/2006 - 04/01/2006

- 04/01/2006 - 05/01/2006

- 05/01/2006 - 06/01/2006

- 06/01/2006 - 07/01/2006

- 07/01/2006 - 08/01/2006

- 08/01/2006 - 09/01/2006

- 09/01/2006 - 10/01/2006

- 10/01/2006 - 11/01/2006

- 11/01/2006 - 12/01/2006

- 12/01/2006 - 01/01/2007

- 01/01/2007 - 02/01/2007

- 02/01/2007 - 03/01/2007

- 03/01/2007 - 04/01/2007

- 04/01/2007 - 05/01/2007

- 05/01/2007 - 06/01/2007

- 06/01/2007 - 07/01/2007

- 07/01/2007 - 08/01/2007

- 08/01/2007 - 09/01/2007

- 09/01/2007 - 10/01/2007

- 10/01/2007 - 11/01/2007

- 11/01/2007 - 12/01/2007

- 12/01/2007 - 01/01/2008

- 01/01/2008 - 02/01/2008

- 02/01/2008 - 03/01/2008

- 03/01/2008 - 04/01/2008

- 04/01/2008 - 05/01/2008

- 05/01/2008 - 06/01/2008

- 06/01/2008 - 07/01/2008

- 07/01/2008 - 08/01/2008

- 08/01/2008 - 09/01/2008

- 09/01/2008 - 10/01/2008

- 11/01/2008 - 12/01/2008

- 01/01/2009 - 02/01/2009

- 04/01/2009 - 05/01/2009

- 07/01/2009 - 08/01/2009

- 09/01/2009 - 10/01/2009

- 10/01/2009 - 11/01/2009

- 11/01/2009 - 12/01/2009

- 12/01/2009 - 01/01/2010

- 03/01/2010 - 04/01/2010

Utopian Turtletop. Monsieur Croche's Bête Noire. Contact: turtletop [at] hotmail [dot] com

Monday, July 03, 2006

Somewhere in his talk-poem “The Sociology of Art,” David Antin proposes a distinction between literal and oral culture. In a literal culture, a person performing a culturally recognizable act adheres as closely as possible to the “letter of the recipe.” In an oral culture, the same act is faithfully rendered as long as the actor follows the general outlines of the recognizable process.

You can see this distinction at work in music: the difference between the “literal” culture of (the vast majority of) classical music, versus the “oral” culture of most popular and folk musics. The wild panoply of differing versions of a standard song of the popular and jazz traditions -- Juan Tizol and Duke Ellington’s “Caravan,” for example -- wouldn’t be possible in a literal culture, even when almost all of the arrangements of “Caravan” from the big band era were mostly written down.

This distinction isn’t fair to the pre-Classical European tradition that has since been absorbed into the Classical tradition. I’m dating the birth of the classical tradition to Mendelssohn’s revival of the music of J.S. Bach, some 75 years after Bach’s death. Before then, classical ensembles almost exclusively played contemporary music or the music of the very recent past. Even though composers had studied Bach all along, Mendelssohn brought the past into the present in a way it had never been before.

Mozart had studied with one of Bach’s sons and with Haydn, and Beethoven had studied with Haydn, and Beethoven influenced everybody subsequent -- but the tradition of Bach’s improvising was dead and gone -- nobody knew what it sounded like by Mendelssohn’s time. Bach had been a champion improviser, and 70 years after his death nobody knew what his embellishments and ornamentations to his printed scores may have been, because the “oral” part of his tradition had died out, probably within his own children’s lifetimes.

I recently picked up a recently recorded CD of tunes by Vernon Duke sung by classical star Dawn Upshaw. Duke had been a classical composer named Vladimir Dukelsky who fled the Russian Revolution as a young man. George Gershwin befriended him and encouraged him to write pop songs and to Anglicize his name. Duke took both pieces of advice. His most famous songs are from his seasonal-travel suite, “Autumn in New York,” “April in Paris,” “Summer in Newport,” and “February in Vladivostok.” (Those last two are a joke based on the oddity that two of his three most famous songs are about seasons in cities; his 3rd famous standard is “I Can’t Get Started.”)

Upshaw phrases poorly. She focuses too lovingly on the literal “trees” of the individual notes at the expense of the “forest” of the phrases. Dang, Upshaw’s individual notes are gorgeous, with beautiful attacks and delicate fades, but I have to strain to hear the meanings of the words. It’s weird. I haven’t given up on her after only a couple listens; I’m enjoying the lovely melodies and pear-like tones despite the perverse phrasing.

* * *

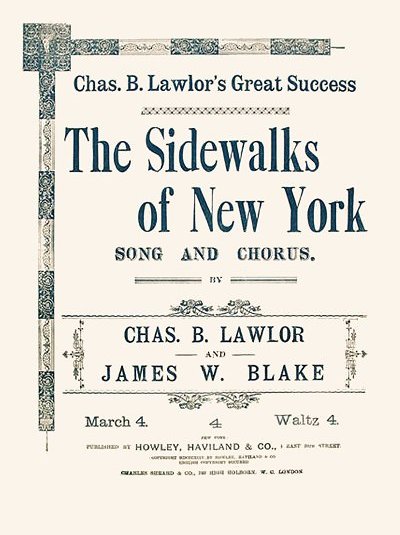

People from literal cultures often make sentimental assumptions about people from oral cultures. The great musician and scholar Mike Seeger heard someone sing “Lovin’ Spoonful” somewhere in the Carolinas in the 1950s, and supposed that the song existed in an oral tradition completely independent of Mississippi John Hurt’s 1920s recording of the song. Maybe Seeger is right, but I’d bet not. I have a recording of a Mississippi drum-and-fife ensemble playing the early Tin Pan Alley hit “Sidewalks of New York” in 1942. A Seeger-ite would posit that the Tin Pan Alley song was a rip-off of an independent Mississippi tradition of sentimental nostalgia for a New York City youth. (It’s a beautifully wistful song.)

* * *

Another literal-culture assumption that makes me scratch my head: When the anthropologists get around to recording the oral arts of oral cultures, we -- the literalists -- seem to do nothing to disspell the assumption that the particular oral arts under present examination have “always” existed in their precise present forms. Strikes me as an unwarranted assumption. Chances are high that 50 years before “contact” with the literal-culture recordists, the song was quite different, if it existed at all.

Comments:

Post a Comment